There’s a decent chance you’ve heard of someone called “the Elephant Man,” even if you couldn’t say exactly when, where, or why. Maybe it was a movie you half-remember watching years ago. Maybe it was a reference that drifted by in a conversation or a documentary, carrying with it a vague sense of tragedy, dignity, and inspirational suffering. The cultural memory is blurry, but the emotional shorthand is clear enough: a severely deformed man, unkindly treated by society, eventually rescued by compassion.

Unfortunately, that version of the story is not just incomplete—it’s actively misleading.

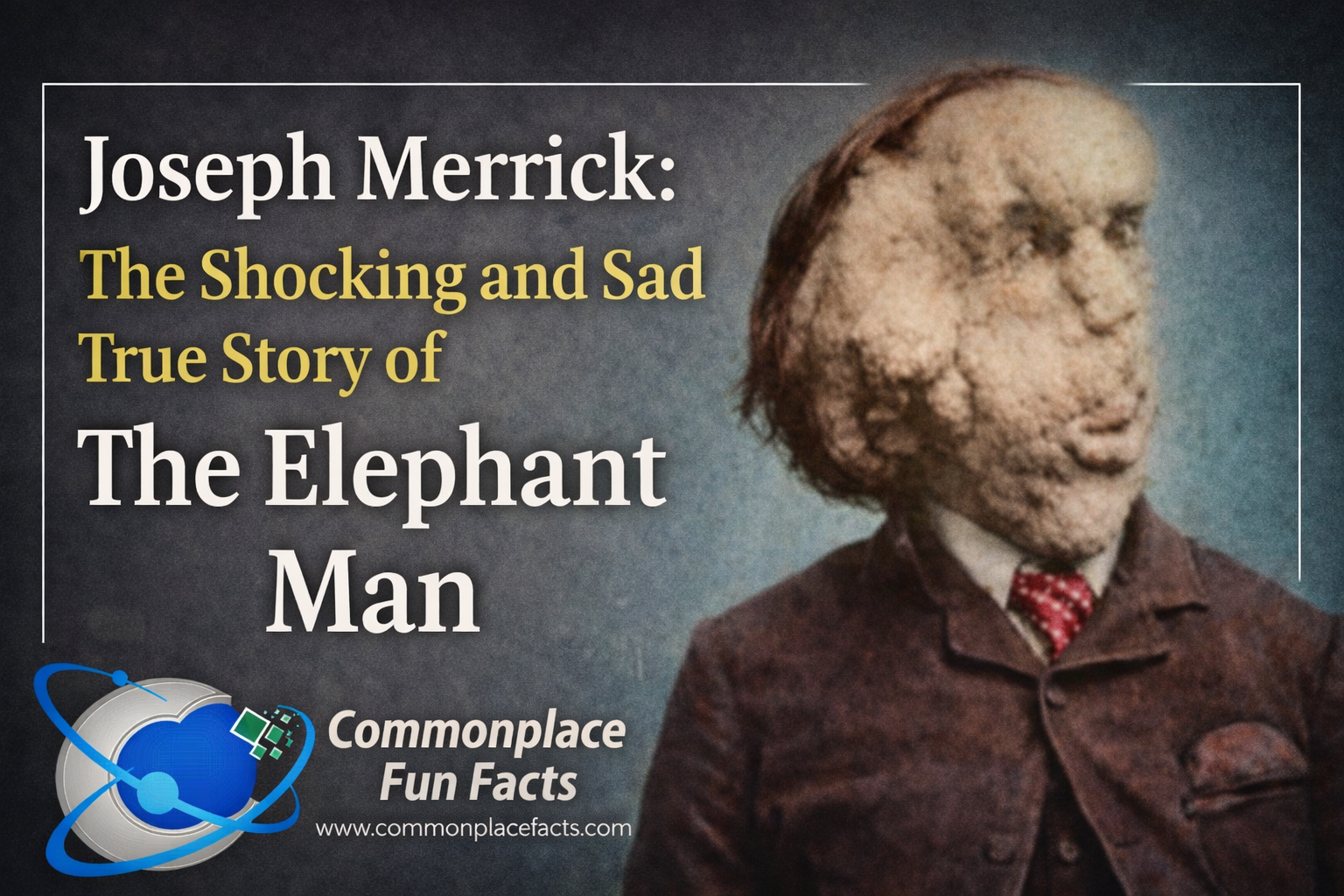

The man at the center of it all was named Joseph Merrick, and while he did live with extreme physical deformities, his life bears little resemblance to the tidy arc popular culture has handed down. He was not simply rescued from cruelty and restored to dignity by enlightened benefactors. What actually happened was stranger, quieter, and more unsettling. Merrick moved from one kind of sanctioned observation to another, from public spectacle to institutional curiosity, from being stared at openly to being stared at politely.

This is not a story about a monster being treated humanely. It’s a story about a human being forced to live inside other people’s ideas of what kindness looked like at the time—and how little those ideas required anyone to stop staring.

Contents

Before There Was a Category

Joseph Merrick was born in Leicester in 1862, and by contemporary accounts his infancy gave no particular cause for alarm. There were no dramatic warnings, no ominous birthroom pronouncements. He entered the world as a child rather than as a lesson, a status he would not enjoy for very long.

The changes in his body began slowly, enough that they were confusing rather than shocking. His skin thickened unevenly, his bones grew asymmetrically, and his face altered in ways that resisted easy explanation. This gradual transformation created exactly the sort of problem Victorian society disliked most: a visible disorder with no immediate category.

Victorian England was a culture in love with classification. It sorted plants, animals, workers, virtues, and even criminals with bureaucratic enthusiasm. When confronted with bodies that refused to cooperate, it did not ask how to accommodate them. It asked how to explain them.

One popular explanation held that Merrick’s condition resulted from his mother being frightened by an elephant while pregnant, a theory that had the dual benefits of being vivid and incorrect. More importantly, it preserved the comforting belief that the world operated on tidy rules of cause and effect, and that unfortunate outcomes could be traced to a single, narratively satisfying moment.

This explanation lingered not because it was persuasive, but because it was useful. It turned a complicated human reality into a story everyone could repeat, which mattered far more than whether the story was true.

One of the enduring ironies of Joseph Merrick’s life is that as adults grew more confident in explaining him, they grew no more accurate. For decades, almost everyone was certain about what was wrong with him—and almost everyone was wrong. During his lifetime, his condition was commonly described as elephantiasis, a term borrowed from a parasitic disease that causes swelling. The label was vivid, memorable, and medically incorrect, which made it perfect for public consumption. It gave people a word they could say with confidence while avoiding the more unsettling reality that they didn’t actually understand what they were seeing.

The more accurate name would not arrive until long after Merrick was gone. In the late twentieth century, medical researchers proposed that Merrick most likely suffered from what is now called Proteus syndrome, an extremely rare genetic condition that causes asymmetric and unpredictable overgrowth of bones, skin, and other tissues. As in the case of the rare condition known as Stone Man Syndrome, it tends to strip away the sufferer’s humanity, turning the patient into a public spectacle. Unlike elephantiasis, it explained why Merrick’s body developed unevenly and progressively. Unlike the Victorian theories, it did not rely on superstition, moral causation, or convenient metaphors. It was precise, dull-sounding, and arrived about a century too late to make any difference to the child who had already grown up without it.

That delay matters. Merrick spent his childhood being explained without ever being clarified, named without ever being understood. The wrong diagnosis didn’t just mislabel his condition; it reinforced the idea that his body was something to be interpreted for the comfort of others rather than accommodated for his own. By the time a correct name existed, it served only the historical record. For Merrick himself, all that certainty arrived after the only person who might have benefited from it was no longer around to hear it.

Learning Early What It Means to Be Seen

School was difficult for Merrick, not because he lacked intelligence or curiosity, but because attention followed him everywhere. Children have never been particularly good at politely overlooking physical differences. They learn very quickly which differences provoke reaction, and Merrick’s appearance provoked plenty.

Mockery escalated as his condition worsened, and teachers possessed neither the tools nor the inclination to manage it effectively. Education slipped away not by decree but by exhaustion. When learning requires constant self-defense, something eventually gives.

Work offered no relief. Factory labor demanded speed, endurance, and bodies that behaved predictably. Merrick’s did not. Attempts at public-facing work were worse, as being stared at while trying to sell something requires a special combination of resilience and humiliation.

Each failure reinforced the same lesson: Joseph Merrick’s worth was being assessed visually long before he spoke.

When Protection Disappears

The death of Merrick’s mother marked a decisive turning point. By his later accounts, she had been his primary defender, the person who treated him as ordinary when the rest of the world hesitated.

After her death, whatever insulation he had within his family disappeared quickly. His father remarried, the household grew more strained, and tolerance wore thin. A son who could not reliably contribute wages was no longer an inconvenience but a liability.

Physical abuse entered the picture, but perhaps more damaging was the quiet recognition that he no longer belonged. When Merrick eventually left home after a violent confrontation, he was not staging a dramatic escape. He was responding to a household that had already decided he was surplus.

The Workhouse Solution

The Victorian workhouse was not designed as a refuge so much as a warning. It offered food and shelter in exchange for submission, hard labor, and the understanding that comfort was not part of the arrangement.

Merrick entered the Leicester workhouse as a teenager and would return multiple times. Life there was regimented, exhausting, and indifferent to personal circumstances. Everyone suffered. That was considered a feature, not a flaw.

Workhouse labor assumed able bodies that responded properly to discipline. Merrick’s body did neither. The system did not bend, because it was not designed to.

Eventually, Merrick reached a bleakly rational conclusion. If people were going to stare at him regardless, perhaps the least terrible option was to be paid for the inconvenience.

The Transactional Honesty of the Freak Show

Victorian freak shows were not quaint curiosities tucked away at the edges of entertainment. By the mid-19th century they had become a thriving commercial phenomenon, part carnival, part theatrical performance, and part social mirror. They weren’t limited to oddities of body and bone; the same crowds that paid to see a “giant” would also queue for sword swallowers, tattooed performers, and anything that deviated from what the culture called normal. The rise of this industry was tied to the broader Victorian obsession with classification: science and spectacle went hand in hand, turning the unusual into a product that could be packaged, explained, and consumed. Freak shows were marketed widely, with elaborate posters and origin stories that often had as much fiction as fact, inviting audiences to believe they were encountering the raw stuff of nature rather than a carefully curated artistic illusion of it.

Some freak shows could plausibly claim a social benefit. Exhibits featuring premature infants, for example, helped popularize incubators at a time when hospitals were skeptical of their value, and that exposure arguably saved lives. But these cases were the exception rather than the rule. Far more often, freak shows operated on a simpler and more reliable principle: human difference could be monetized. Physical deformity, unattractive appearance, sheer misfortune, or merely a willingness to be punched in the face for a fee were repackaged as curiosities, inviting audiences to stare, marvel, and reassure themselves that whatever was wrong was safely contained on the other side of the platform.

That blend of commerce and curiosity was more than just entertainment; it was a performance of social power. Walking into a freak show was not a neutral act: it was an invitation to stare and to feel something about what you saw. Different people looked for different things — horror, pity, amusement — but the setup encouraged a kind of participation where spectators could define themselves against the bodies on display. Scholars have observed that this dynamic wasn’t simply idle gawking, but a way of reinforcing categories of normal and abnormal, self and other. The body on stage became a symbolic boundary marker, telling audiences something about what they were by showing them what they weren’t. In that sense, freak shows functioned less like neutral spaces of curiosity and more like ideological stages where Victorian ideals of class, race, ability, and beauty were enacted, reinforced, and naturalized.

For the performers themselves, the situation was paradoxical. Most of the people exhibited had few options in a society that offered them little protection and fewer opportunities. Jobs in factories, farms, or shops were often impossible for someone with significant physical differences; many would otherwise have faced institutionalization in workhouses or asylums. In that context, freak shows — exploitative as they often were — offered a rare avenue for income and a measure of autonomy. The fact that these exhibitions were grounded in profit did not erase their human cost, but it does complicate the easy narrative of villains and victims. Many performers, including those with disabilities not much different from Merrick’s, chose to participate not out of vanity or theatrical ambition, but out of necessity — to keep a roof overhead, to buy food, to escape the worse fate of obscurity or neglect. In other words, the freak show was both a symptom of social failure and, for some, a reluctant survival strategy.

Joseph Merrick approached showmen voluntarily, a fact that complicates the story without redeeming it. The decision was not empowering, but it was practical. The terms were explicit. People would look. He would earn money and be labeled as “The Elephant Man.”

The arrangement was dehumanizing, but it did not pretend to be anything else. No one claimed Merrick was benefiting spiritually from being displayed. No one suggested attendance was an act of charity. The cruelty was obvious, and that honesty counts for something, even if it doesn’t count for much.

The Elephant Man: From Spectacle to Specimen

When Merrick’s freak show phase began to yield mixed returns — decent crowds in provincial towns but limited excitement in London — his proximity to the London Hospital turned an already weird career into something stranger. His exhibit wasn’t hidden away in a grimy tent; it was right across from a center of medical learning. This brought him to the attention of Frederick Treves, a surgeon who saw Merrick not just as a curiosity to be gawked at, but as something that might be… studied. The language changed. The venue changed. The implications didn’t.

Treves examined Merrick and, perhaps understandably, began to write about him in medical circles. What had been a public entertainment became what doctors called a “case study.” Merrick was measured, described, and presented to colleagues in lecture halls. He was valuable in the way specimens are valuable: as evidence of something unusual. In those early clinical notes, the focus was almost entirely on the body and its deviations, while the person inside it receded. The subtle shift from showman’s stage to scientific lecture often gets framed as a rescue, but that framing depends on what you think rescue means.

The transition did bring material improvements. Merrick was offered shelter and care that his itinerant show life never provided. But it did not stop the spectacle so much as rebrand it. Instead of paying a penny at a storefront, visitors now paid social visits to the hospital, murmured sympathetic phrases, and reassured themselves that this time the staring was compassionate and scientific. Merrick was no longer a ticketed attraction; he was a sanctioned curiosity. He was an object of study whose existence justified exhibitions of a different kind — polite tours, earnest questions, and constant observation by professionals who saw their role as utterly humane.

In the shift from the freak show to the consulting room, the essential dynamic didn’t disappear. It just changed shape. The crowds thinned, the lighting improved, and the language became clinical, but the underlying arrangement — a body set apart for others to see and define — remained the same. Merrick’s life after public exhibition was not a withdrawal from spectacle. It was a repackaging of it under the banner of science and sympathy. And in that repackaging, the person became a category, and the category became the story.

When the Law Turns Away

As public attitudes toward freak shows shifted and legal pressure mounted, Merrick’s career in that world ended abruptly and badly. A European tour left him robbed, abandoned, and stranded without resources.

He returned to England physically ill and emotionally shaken, scarcely able to advocate for himself. Police intervention brought him back into the orbit of doctors who now viewed him less as an object of curiosity and more as a responsibility.

The Hospital as Refuge

Merrick was offered permanent residence at a London hospital, where he would remain for the rest of his life. This is typically framed as rescue, and in many ways it was. He was fed, sheltered, and spared further exhibition for profit.

It was also confinement, though described with considerably better vocabulary.

His room became a destination. Visitors arrived with sympathy rather than tickets. Donations replaced admission fees. The gaze continued, but it was now wrapped in the language of compassion.

The Performance of Kindness

Victorian philanthropy excelled at turning suffering into moral experience. Merrick became an object lesson in sympathy, a person people could look at in order to feel something meaningful and then leave reassured of their own decency.

The emotional response mattered more than the relationship. Knowing Merrick was optional. Feeling about him was sufficient.

The Man Still Inside

Despite everything, Merrick maintained a rich inner life. He read widely, developed routines, and constructed elaborate paper models of churches and buildings from scraps, patiently imposing order where his own body refused to cooperate.

He formed friendships with hospital staff who treated him as a person rather than a project. He had preferences, habits, and opinions. He was acutely aware of how others perceived him and learned to navigate that awareness carefully.

One of the most telling moments of his life came when he met a woman who treated him without fear or revulsion. He was deeply moved, not by romance, but by normalcy. That reaction says less about sentimentality than it does about how rarely the world afforded him simple recognition.

Who Got to Tell the Story

Much of what we think we know about Joseph Merrick comes filtered through the memories of Frederick Treves, who knew him only after his life had become institutional. Decades later, he published his recollections as The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences, shaping how Merrick would be remembered for generations.

The account was affectionate and influential, but it was also incomplete and occasionally inaccurate. Merrick had never fully confided in him about his early life, leaving gaps that were quietly filled with implication. Even Merrick’s name was altered without explanation, a small but telling reminder of how easily authority can overwrite evidence.

The surgeon also portrayed Merrick’s former showman as a singular villain, an image the showman vehemently disputed. Each man was writing for a different audience, protecting a different professional identity, and telling a version of the story that cast his own role in the best possible light.

Merrick himself had no such opportunity. His voice reaches us indirectly, through fragments preserved by people with narratives of their own to maintain.

The Uncomfortable Legacy

Merrick’s physical condition shaped even his most basic routines. Because of the size and weight of his head, he slept sitting upright and was warned against lying flat.

One night, he tried anyway. He wanted, quite simply, to sleep like other people. The attempt killed him.

Joseph Merrick died at twenty-seven. His body remained, as it had in life, an object of interest. His skeleton was preserved. His story continued through plays, films, and books that reshaped him into inspiration, metaphor, and symbol, all under the unfortunate title, “The Elephant Man.”

Each retelling softened discomfort and reduced agency, smoothing a complicated life into something reassuring. He became useful again.

The problem with the story isn’t just that it leaves things out. It’s that it teaches us the wrong lesson. It encourages us to locate the cruelty in obvious places—rowdy crowds, grimy exhibition halls, coarse showmen—while giving everyone else a free moral pass. Merrick’s life suggests something far less comforting: that compassion, when wrapped in authority and good manners, can coexist quite comfortably with control, objectification, and the quiet erasure of agency.

Merrick’s story does not indict monstrous individuals so much as ordinary systems functioning efficiently and politely. No villains are required. Everyone had reasons. Everyone spoke kindly.

That is what should unsettle us.

This is not a story about how far we have come. It is a reminder of how easily sympathy can coexist with control, how looking can masquerade as caring, and how politeness can anesthetize conscience. The Victorians did not invent these tendencies. They simply organized them very well.

You may also enjoy…

Stone Man Syndrome: The Disease That Makes You Into a Human Statue

Stone Man Syndrome: What Is It? Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP), sometimes referred to as Stone Man Syndrome, is an extremely rare disease of the connective tissue. A mutation of the body’s repair mechanism causes fibrous tissue (including muscle, tendon, and ligament) to be ossified spontaneously or when damaged. Essentially, it causes a second skeleton to…

How Freak Shows Revolutionized Medical Care for Babies

Discover the extraordinary history of premature baby care and how incubators in amusement park freak shows laid the foundation for modern neonatal medicine.

Oofty Goofty — The Man Who Made a Living Getting Beat Up

Dive into the bizarre life of Oofty Goofty—19th‑century sideshow star who charged crowds to beat him up, survived tar-and-hair tarades, and defied real pain.

Leave a Reply